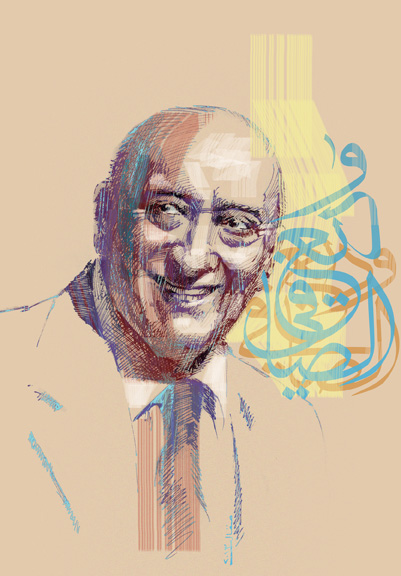

Wadi al-Safi by Mamoun Sakkal for Al Jadid

Wadi al-Safi’s voice carried over almost a century.When Lebanese singer and composer died on 11 October 2013, at nearly 92 years of age, his professional career which began when he was only 12 years old, spanned 80 years. Born Wadi Francis on the first of November 1921 to a poor family in the Mount Lebanon village of Niha in Al-Shuf district, his father, Beshara Gabriel Francis, a police officer, and mother, Shafiqa Shadid al-’Ujil, moved their family to Beirut when Wadi was nine. In Beirut, he attended a Catholic school where he began singing at its religious choir. That early experience of chanting religious hymns stayed with Wadi until his final days.

At the age of 12, Wadi dropped out of school to help support his family by singing for pay at local events. His singing impressed audiences with the strength and sweetness and range of his voice, causing people to predict a great future for him. At 17, he learned of a singing competition at the state-run radio station, the only avenue at the time to a proper musical career path, as well as the possibility of fame. Wadi auditioned and, out of the 40 competitive contestants, placed first. From this recognition he obtained employment as a professional singer at the radio station’s music department.

Wadi perfected his style and music ability from an early age, and he became a pioneer of Lebanese folk music. Wadi had learned to play the rababa, thenthe violin when he was young. Next, he learned to play the oud, which he continued to use for composing as well as on stage accompaniment during most of his concerts. Growing up, he had developed his singing style by listening to the Egyptian stars that dominated the Arab music scene – singers such as Muhammad Abd al-Wahhab who later collaborated with him. Wadi’s grandfather taught him the Lebanese folk style that eventually characterized the bulk of his repertoire, as well as many poems and tunes from the village tradition. The Lebanese artist Halim al-Rumi, who discovered the legendary singer Fayruz and his own daughter Majida al-Rumi, encouraged Wadi early in his career to emphasize Lebanese folk music, believing it suited the singer’s so-called mountain-style voice. This opened many doors for Wadi when he later participated with the Fayruz and the Rahbani Brothers in the first Baalbeck International Festival in 1957. Here, the initially critical art community took notice of Lebanese folk music, recognizing it as a legitimate genre worth preserving.

Wadi Francis’ ambitions soon surpassed the limitations of the radio station. Discarding the European-Christian “Francis,” he selected the stage name Wadi al-Safi, meaning Wadi the Pure. This helped him to gain greater acceptance in the new cosmopolitan Beirut and throughout the Arab World. Shortly thereafter, al-Safi immigrated to Brazil, following in the footsteps of his father and grandfather, who had each traveled to Brazil as young men in order to earn the money needed to start their families in Lebanon. Although he returned to Lebanon after only four years, this trip represented a major turning point in the young man’s singing style. When he sang to the large Lebanese community in Brazil, al-Safi noticed that the most popular songs evoked nostalgia for the homeland. He found himself again living overseas during the 1975-1990 civil war, gaining audiences, as well as additional citizenships, in European and Arab nations, where he catered to Lebanese expatriates with folk song genres like abu-zulluf, dal‘una, mijana, and ‘ataba. This became a lifelong hallmark of his style. The majority of his songs described the beauty of the countryside, village life, and family relations, as well as the appeal of patriotism. Al-Safi made sure to craft these songs with a positive outlook, and worked hard to bring smiles from his audiences. In fact, he interacted a great deal with his concert audiences, often stopping the program to welcome people with characteristically warm colloquial phrases. This contrasted with other singers of the same period: Farid al-Atrash, for example, became famous for his sad songs.

In Lebanon, Wadi joined forces with the Rahbani family, developing the new Lebanese urbanized folk style. He co-starred with Fayruz, and sometimes with Sabah, in many of the festivals whose music came to embody the new Lebanese song as a worldwide genre, popularizing the Lebanese dialect throughout the Arab World. The Rahbani brothers derived material from the folk style but sophisticated and Westernized the lyrics and instruments to appeal to the new and critical cosmopolitan audiences. In addition to composing many of his own songs, Wadi demonstrated versatility and talent by singing songs composed by Asi and Mansur Rahbani, as well as their younger brother Elias and Rahbani team member Filimun Wehbe. Egypt’s greatest composers of the period, artists like Farid al-Atrash, also sought Wadi out. Al-Atrash composed the smash hit ‘Alallah T‘oud, with its nostalgic theme of waiting for the return of a loved one from afar. Muhammad Abd al-Wahhab, composed Wadi’s hit song ‘Indak Bahriyya Ya Rayyis, concerning a ship captain, a key figure with Lebanese expatriates, who traveled mostly by sea. (In an interview, Wadi classified al-Wahhab’s song as a “cute experiment” since it did not fit the composer’s usual sophistication. Wadi also joked that Wahhab was jealous that he had accepted a song from al-Atrash and so offered him one as well.)

In his repertoire of several thousand songs covering religious, nationalistic, and romantic genres, the singer collaborated with a wide variety of lyricists. Art historian Victor Sahab’s book about Wadi al-Safi lists thousands of the singer’s documented songs. In addition to the beautiful pre-composed songs in his repertoire, audiences also enjoyed Wadi’s vocal improvisations, called mawawil (singular mawwal). Although he employed these non-rhythmic free forms as openings to songs, they began to take on a life of their own. Since recordings exist of most of these improvisations, many of Wadi’s imitators perform them verbatim in his ‘urab style, with its subtle musical microtones. Wadi used ‘urab to help audiences reach a state of ecstasy called tarab.

Mawawil improvisations used vivid imagery to describe the beauty of the country: mountains that stood up to time, rivers that flowed with honey, and valleys that could not be conquered. In addition, common refrains embodied the call to return to the homeland to rebuild the country, as well as the admonition to listen to paternal advice, to avoid arrogance and, of course, to always remember Lebanon and its great mountain, Jabalna.

Wadi’s repertoire contained numerous examples of the mijana and ‘ataba genres, nonmetric strophic folksongs followed by metric choral refrains, forms popular throughout the Levant. These began as a nomadic Bedouin genres that were improvised by poet-singers accompanying themselves on the rababa. Wadi employed a trick learned from the Rahbanis, replacing the rababa with a small ensemble, comprised of traditional and Western instruments. He also sang in the Bedouin style known as lawn badawi in such popular songs as Habibi wa Nur ‘Aynay, with lyrics by ‘Abd al-Jalil Wehbi and music by Wadi. This style evoked the Bedouin ethos, modernized and framed by urban instrumentation.

Wadi, who loved music and cheering crowds, never thought of retiring. Even in his later years, he did not hesitate to experiment or collaborate. He appeared in films and video clips, recorded duets with younger singers and even toured with the young Spanish flamenco singer and guitar player, Jose Fernandez, who learned Wadi’s songs in Arabic. Some over-interpreted this collaboration as a West meets East scenario, but this did not include any compromise on Wadi’s part.

With the help of one of his sons, who accompanied him on the violin and managed his affairs, Wadi continued to perform and make television appearances until his last days. Late in his career, he also composed for his daughter-in-law, Siham Francis, also known as Siham al-Safi. Only weeks before his passing and despite apparent illness, Wadi appeared on a popular television music program hosted by a Syrian singer who had taken a position against the Assad regime. In his last public appearance, the non-political Wadi felt compelled to call a press conference to explain that appearing on that show was never intended as a political statement about the war and that he appreciated the Syrian government which had warmly hosted him in Damascus throughout his career. Days later, Wadi was transported to a Beirut hospital and passed away, just short of his 92nd birthday. Homemade videos taken by his relatives showed Wadi happy until the end, cheerfully singing religious hymns in bed and, as always, welcoming visitors.

Beloved in his homeland and worldwide, Wadi’s death was revered in the New York Times which reiterated the eloquent words of Lebanese President Michel Suleiman, “His passing is a loss to the nation and every Lebanese home. He embodied the nation through his art.” Wadi’s many awards included military and academic honors and visionary titles, such as the Frank Sinatra of the East. During and after his lifetime, the singer and composer also is studied by many musicologists. It has been said that Wadi jokingly referred to himself as the “old man wolf,” since the wolf (saba‘) has long symbolized fearlessness in songs about hunting. Given his religious and patriotic work, as well as his insistence in maintaining high standards of musical skill and enchantment in even the simplest of folk songs, Wadi, has, appropriately, become known as the Saint of Tarab, serving as a role model for both past and future generations of artists.

This article appeared in Al Jadid Magazine, Vol. 18, No. 66, 2012-2013.

Copyright © 2013 AL JADID MAGAZINE