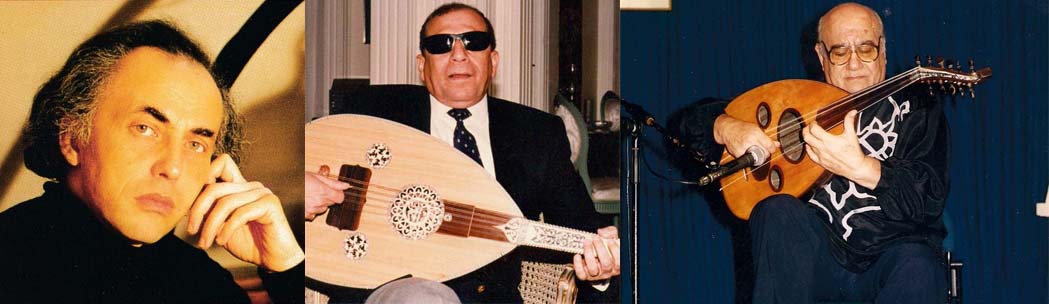

The past few months witnessed the loss of three Arab musicians who were pioneering giants and history-makers - Sayyid Makkawi, Munir Bashir and Walid Akel - three different men on different paths: Makkawi, an Egyptian composer and singer who had reached a career peak and was nearing retirement; Bashir, an Iraqi oud player and composer with international acclaim; and Akel, a Lebanese pianist prodigy who performed Western classical music with a vision to invigorate his art in Lebanon.

Sayyid Makkawi's Five Thousand Tunes

After 52 years of singing and composing, Sheikh Sayyid Makkawi died at age 70 in Cairo after a Ramadan trip to Beirut, where he fell sick. With thousands of compositions to his credit, Makkawi is, literally, the last of a group of Egyptian religiously-trained sheikhs who turned to music and became giants, including Sheikh Salamah Hijazi, Sheikh Imam, Zakariya Ahmad and the ever popular Sheikh Sayyid Darwish.

Makkawi's primary contribution to Arabic music was in popularizing tarab songs. Tarab, the feeling of ecstasy associated with music appreciation, was in the domain of long art songs. Like Sayyid Darwish before him, Makkawi was more in touch with people at all levels, and performed for the people, often about themes of relevance to their daily lives. Popularizing the music, however, did not come at the expense of the quality of his work, and that brought him head and shoulders above a crowd of song-writers.

As proof of his high quality, Makkawi was sought after by the best, including Umm Kulthum, for whom he wrote the hit song "Ya Msaharni," Layla Murad, Warda, Mayyada, Sabah, and Faiza Ahamad. He wrote the ever-so-cute song, "Is'al Marra -Allaya" [Ask for Me Once in a While] sung by Mohammad Abdul Muttaleb. He even surprised his colleagues by working with Shukuku, the folk comedian and singer. Few are aware that Sayyid Darwish composed popular songs, such as those for the hit comedy play "Madrast al-Mushaghibeen" [School of Trouble-Makers], starring the noted actor-comedian, Adel Imam.

As demonstrated in his flagship song "Ya Msaharni," he maintained the rules of manipulating the Arabic modal structure (maqam) and percussion without compromise. He simply wrote good music the old-fashioned way and did not need to bend the rules to create something new-a controversial theme even today among contemporary composers. His work combined simplicity and depth in an unrivaled way, typically utilizing the "call and response" mechanism of composing.

Blind from childhood due to medical mishandling in his poor community (the same conditions that led to the blindness of author Taha Hussain), Makkawi did not let that depress him. He often joked about the subject, telling reporters that his hobbies included bicycle racing. His best blindness story was once reported in "As Safir" magazine: He was once invited to perform the call to prayer at the prestigious Sit Zainab mosque in Cairo, and was led to a chair and handed a microphone. His host, however, asked to him to rest for a few minutes since it was still early for the call to prayer. The tired Makkawi fell asleep and did not wake up until it was past the prayer time. That was not the bad part; when he woke up, unable to see his surroundings and forgetting where he was, he felt a microphone in his hand. He cleared his throat and enthusiastically sang the latest song by Mohammad Abdulwahab, "al-Gundul." For miles around the mosque, the shocked neighborhood could not believe what they heard emanating from the mosque's loudspeakers. Surprisingly, people did not interrupt him until he finished the song, at which point the officials were reportedly ready to "kill him." He got away unharmed.

Being a blind child quickened his family's decision to enroll him in an "al-kuttab" Quranic school, where he with his beautiful voice excelled as a child reader of the Quran. In secret, however, he listened to records on his father's gramophone and sang popular songs. Not wanting to offend his family or teachers, he kept his ambition to sing and compose to himself. He was 20, when after meeting two producers who encouraged him, he took his chances in the business. He quickly lost whatever income he was making from Quranic chanting and began the life style of a poor artist. He could not afford a tutor to learn the musical scales (the Arabic word for scale is the same as for ladder) and joked that his poverty made him "fall off the ladder."

Makkawi's big break came when a known poet collaborated with him on a musical called "The Big Night," in which he composed all the tunes and sang most of the songs. The surprising success of the unknown musician placed him in high demand ever since. He ended up composing a dozen musicals as part of his works, which ultimately included a catalogue of 5,000 tunes.

Makkawi succeeded because he had a natural tendency to produce music that everybody could relate to. Whereas some songs can only be enjoyed in a certain mood, Makkawi's work was, like his personality, never imposing, and could be accepted at any time. During a recent trip to the University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA), where he was honored by ethnomusicology Professor Jihad Racy, one could see first-hand that the man was humble and maintained a sense of humor, yet could move the spirit of all around him, as did his music.

Munir Bashir The Improviser

"Ironically, the West accepted him for his Eastern music while the Arab world favored musicians who adopted elements of Western music"

Munir Bashir was universally considered the best soloist oud player alive and one of the greatest of all times, in the company of Mohamad Qasabgi, Farid al-Atrash and Sharif Haydar. Born in the Iraqi city of Mosul to an Assyrian father and Kurdish mother, Munir was only five when his father started teaching him and older brother Jamil the basics of oudplaying. His father, who was also a poet, stressed the purist musical traditions in the spirit of living in Baghdad, the old capital of the Abbassid caliphs. During the Abbassid period, Mosul produced Ishaq and Ibrahim al-Mouseli, who, along with former student Ziryab, who had escaped Iraq and settled in Andalusia, are considered the fathers of Arabic music as we know it today.

The Bashir children were compelled to live up to that honor and responsibility, and both became apprentices of master instructor Sharif Mohiedin Haydar. Jamil excelled beyond his father's expectations, later developing his own style on the oud, and also played the violin.

It did not take long for Munir, however, to master the subtleties of playing the instrument. He became an unrivaled virtuoso, thus giving the oud the respect it once had in ancient Baghdad. He later followed in Haydar's footsteps as a professor at the Iraqi Academy of Art and also held the job of music director in the country's broadcasting company, where he cynically likened government officials in charge of making decisions on music to "barbers supervising a surgery."

Dissatisfied with his musical progress, Bashir traveled to pursue higher education in Budapest. He married a Hungarian woman and, in 1965, obtained a doctorate and a quick appointment at the Hungarian Academy of Science as a lecturer in folk art. At various times in his life, he had maintained residences in Iraq, Lebanon and Jordan (where he was awarded a medal by the king), but spent most of his later years at his home in Budapest, where he died of a heart attack at the age of 68.

Bashir's approach to performing was centered on respecting the oud. As a result, he "exploded" the instrument and played it in ways not fully appreciated before. Bashir even discovered a connection between his music and Sufi spiritual traditions. That was accidental and happened only, when, to his surprise, he was invited to a Sufi conference in the United States, since the organizers appreciated the spirituality of his work. He later reportedly came to believe in the music's power to heal sicknesses and physical handicaps.

Despite the fact the he had hundreds of compositions recorded, he is known for his improvisations. He was indeed the king of improvisation (taqsim). And although with a higher education background, he learned the theory of Arabic modal structures (maqamat) in a non-academic way, in the traditional style of apprenticeship. Later in his career, some critics wrote that Bashir excelled in two particular maqams more than others: Shad Arban, because it was easier on the Western ear, and Rast, the fundamental Arabic maqam, implying that he solicited Western acceptance.

Regardless of these insinuations, he had an intuitive feel for the art and the instrument of Ziryab. The latter had added the fifth string to the oud and was the first to use a feather for a pick; to this day even a plastic oud pick is called a feather (risha). Incidentally, a young contemporary Lebanese oud player called Charbel Rouhana added a sixth string to his instrument. While Ziryab's fifth string was a low one, for base resonance, Rouhana's is a high string for added range. Haydar also reportedly experimented with a sixth low string, but the standard instrument remains as left by Ziryab with only minor changes in the tuning. In mutual admiration, Bashir proclaimed young Rouhana to be his "son."

Rouhana is the cousin of the Lebanese musician Marcel Khalife; Bashir's Lebanese connection also included important work with the Rahbani Brothers, and oud recordings of some famous Fairouz songs. In fact, Bashir was "discovered" in Beirut by Swiss ethnomusicologist Simon Jargy, who invited him to perform in Geneva, thus moving him to the international arena, in which he found recognition and comfort. Interestingly, later in his career, Bashir criticized the Rahbanis for their excessive Westernization. Bashir also criticized Mohammad Abdulwahab for adopting elements of Western music, and in doing so, he joins a list of purists who also criticized Abdulwahab in articles and interviews. This list includes Sayyed Makkawi, who called Abdulwahab a traitor, and Sabah Fakhri, who sings in purely traditional Arabic style to this day.

The fantastic improvisational style of Bashir, which had earned him awards from heads of states on every continent, was clearly art music, not popular music. In fact, he is not particularly well known at a grass-root level, and some of the musically uneducated mistake his work for Turkish music. "Alwasat" magazine reported that Bashir once commented that the Egyptian populace did not know of him because he did not sing while playing (probably making reference to Farid al-Atrash) and because he did not sit behind a singer, either (probably referring to Mohamad Qasabgi, Umm Kulthum's oudist). He was a little bitter that the West accepted him more than the Arab world and wondered why Arabs could not embrace an "independent musician!" Ironically, the West accepted him for his Eastern music while the Arab world seemed to favor musicians who adopted elements of fashionable Western music.

The influence of Turkish style, which comes from Haydar, and Indian style (where he borrowed the idea of a brief silence from Indian improvisers, which was unsuccessful with Arabic audiences) as well as his physical playing technique and fingering, gave Bashir a unique and recognizable sound. He often spoke of the art of listening and listening to art, and stressed the purity of the music of the Arabs. Towards that end, he helped found several music schools to pass the legacy on to future generations.

Walid Akel - Without Music, Life Would be an Error

Unlike Sayyid Makkawi, the sheikh who turned into a prolific composer of Arabic music for Arabs, or Munir Bashir, the instrumental specialist who improvised Eastern music for the whole world to enjoy, Walid Akel was an Arab who played classical Western music on a Western instrument.

Jihad Racy, professor of ethnomusicology at UCLA, saw parallels between Bashir and Akel: Bashir proved that an Arab musician could reach Western audiences through Arab art, and Akel proved that an Arab musician could reach Western audiences through Western art. They both gained international acclaim for these accomplishments. Noted similarities between the two instrumental specialists include the fact that they both lived and died in Europe, developed an interest in Sufism, and cared about educating the next generation in music.

At age 14, while his friends played soccer on open fields, Walid Akel took up the piano, quickly realizing it was his calling. His family and community, recognizing the prodigy among them, encouraged him. At a concert in Baalbek, he once met a famous Russian composer named Richter who was amazed that the young man knew small details about his life and work. He spent time with his fan, encouraging him to pursue music without even hearing him play thus giving him the boost he needed. The Russian connection remained with Akel the rest of his career, as he later recorded the works of Russian greats such as Prokofiev, Rachmaninov and Scriabine.

Akel moved to Paris to pursue a higher education, establishing a residence there. He lived with a cat and four pianos until his death at age 52 during heart surgery. With all his tours and busy recording schedule, however, he made time for frequent trips to Lebanon, where he performed at well-attended concerts, maintaining a connection to his heritage, and making a contribution to Lebanese music education. Akel, like Bashir, was aware that his culture favored singers and ensemble musicians over solo instrumentalists, but he succeeded in showing Arabs tarab of a different flavor. In the process, he inspired many Lebanese pianists who are gaining international acceptance in his footsteps; in fact, he was a trendsetter.

The eccentric and intelligent pianist was known to have a hot temper as well as demanding strict accuracy and exactness in his music, typical characteristics of very highly sensitive musicians. His feelings showed in his music, and his interpretations often rivaled the intent of the original composers in their beauty. No wonder An-Nahar newspaper called him a Sufi; his music reflected his spiritual richness and emotional depth. Although he was highly selective in what he played, he did try many periods of Western music, and particularly the Baroque, producing recordings of Johann Sebastian Bach. It appeared that his favorite composer was Franz Joseph Haydn, whom he considered a genius.

He played his works at every opportunity and is reported to be the only pianist to record his complete work, including previously unpublished compositions discovered by a Vienna museum-an effort that took seven years. Akel was very well coordinated, and sought out difficult pieces which emphasized the left hand to stress his skills, although he was by no means showing off; he had a philosophical interest in complex work.

This philosophical angle on life led him to do something which surprised the music community: He found the musical compositions of European poet and philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche and recorded them. Only a few specialists knew that Nietzsche, one of the most provocative and influential thinkers of the 19th century, also composed music, and once Nietzsche wrote that without music, life would be an error. This little secret was of great interest to Akel, the thinker, the man who sought challenges and overcame them.

This article appeared in Al Jadid Magazine, Vol. 4, No. 23, Spring 1998.

Copyright © 1998 AL JADID MAGAZINE