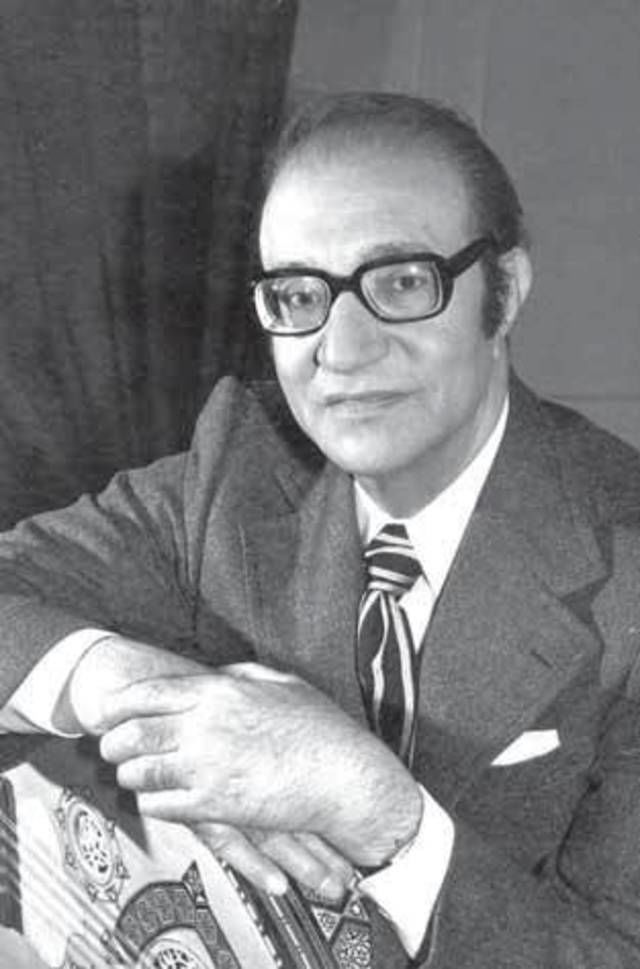

A web-based image of Muhammad Abdul Wahab.

From the 1930s to the 1970s, Mohammed Abdul Wahab was, to the vast majority of Arabic-speaking people, a giant in Middle Eastern entertainment. Every Arab who could afford it bought his records or tapes and listened for hours to his singing on radio and television. His captivating voice brought to their mind the glorious days of Arab culture — when Arabic music and song were the epitome of merriment. His rendering of a melody of the classical poetry from the Arab's golden age and that of their modern struggle against Western colonialism inspired his listeners to feel pride in their rich heritage.

I remember in the 1950s being bewitched by his voice as he sang these words of Ahmad Shawky, an Egyptian poet who became famous in the early part of this century: "Greetings to the gentle breezes of River Barada, Never-ending are the tears, O glorious Damascus. France knows the blood of our martyrs well And knows that it is truth and Justice."

These words imbued me with an appreciation of Arab history and entertainment and, at the same time, gave me immense enjoyment.

Mohammad Abdul Wahab, modern Egypt's best-known singer/composer and actor, died at 90 of heart failure on May 3, 1991, after a musical career spanning 74 years. In those decades, he rose from a humble beginning to become the star of Egyptian songs and a legend in modern Arabic music and melody. Dubbed the "musician of generations," his music delighted people of all ages for years. During his long career, which began in his teens, he composed for himself and other leading Arab singers over 1,800 romantic and patriotic songs. His compositions for the late Umm Kalthoum, the most fabulous Arab songstress in history, gave both artists great fame.

Abdul Wahab fell in love with music and acting as a child, joining a drama troupe at seven. Later, he began to sing at religious festivals. His family wanted him to study religion at Al-Azhar University, but he rebelled and continued pursuing his passion for music. He looked at traditional Arab melodies at the Arab Music Club (now the Institute of Arab Music). He followed this by becoming familiar with Western music at the Bergran School in Cairo.

In the years to come, his remarkable musical memory and fine baritone voice helped him achieve great popularity and influence among the young in music and song. For decades, his improvisation on the oud, composing and singing captivated millions of Arabs and won him great fame.

His early musical career coincided with the revival of Arabic music in the Middle East. Always thinking of new ways to enrich traditional songs, he often combined the oriental quarter-tone melodies with Western themes. Representing a generation in transition, he is responsible for far-reaching changes in Arabic music and is credited by art critics for giving modern Arabic songs their current musical form. His superimposition of a mixture of Western musical instruments on a foundation of Arabic melodies captured the hearts of millions and made him a much-loved musical personality.

Besides his compositions and singing, he became a well-known actor. His first movie was produced in 1933. Until 1946, he starred in six other films regularly screened on television throughout the Arab countries.

In the 1920s, Abdul Wahab became a close friend of the late poet Ahmad Shawky and set that well-known bard's verses to music. A poet laureate of Egyptian King Farouk, Shawky helped Abdul Wahab socially, and he became a traditional star at princely parties. In the ensuing years, his association with the opulent aided in his climb to stardom and earned him the title "singer of princes."

A soft-spoken, tall, and bespectacled man, Abdul Wahab continued in his songs to exalt the wealthy until the Egyptian monarchy was overthrown in 1952. After the revolution led by young nationalist army officers, his view of life radically changed. His songs became more inspiring and patriotic, and he produced some of his finest works. Among these were "The Eternal Nile," "Damascus," and "Palestine," as well as the musical scores for the national anthems of Egypt, Oman, and the United Arab Republic. His last song, "Min Gheir Ley" (Without Asking Why), composed a few years before his death, is said to have salvaged the Egyptian song industry, which had been in the doldrums.

Abdul Wahab's singing was prevalent in the Arab world, and during his lifetime, most Arab countries acclaimed him and his works with decorations. Egypt honored him with a vast military funeral at the Rabia al-Adawiya Mosque in Cairo. The prime and foreign ministers led a six-horse carriage procession carrying his coffin, followed by defense, interior, and culture ministers. The procession also included Arab ambassadors and scores of well-known actors, musicians, and singers, many weeping as they walked behind the coffin.

Soldiers and police, hooking arms, formed a human shield around the procession, which was preceded by bearers of flower wreaths and the medals he had been awarded in his lifetime. Many mourners lining the streets cried as they rendered their last tribute to the father of modern Egyptian song.

Egyptian media coverage of the funeral was equal to that afforded a prominent world figure. For days after his death, newspapers covered his works, and radio and television stations continuously aired his songs and movies. With the passing away of Abdul Wahab, the Arab world has lost the founder of contemporary Arabic music. For over half a century, his composing and singing — he was still writing when he died — appealing to both young and old made him a beloved figure. This is best reflected by a banner raised during the funeral procession, which read: "Adieu to Egypt's fourth pyramid."

*Habeeb Salloum (1924-2019), who lived in Canada, wrote frequently about Arab culture and arts.

This article appeared in Al Jadid Magazine, Vol. 1, No. 2, December 1995.

Copyright © 1995 AL JADID MAGAZINE