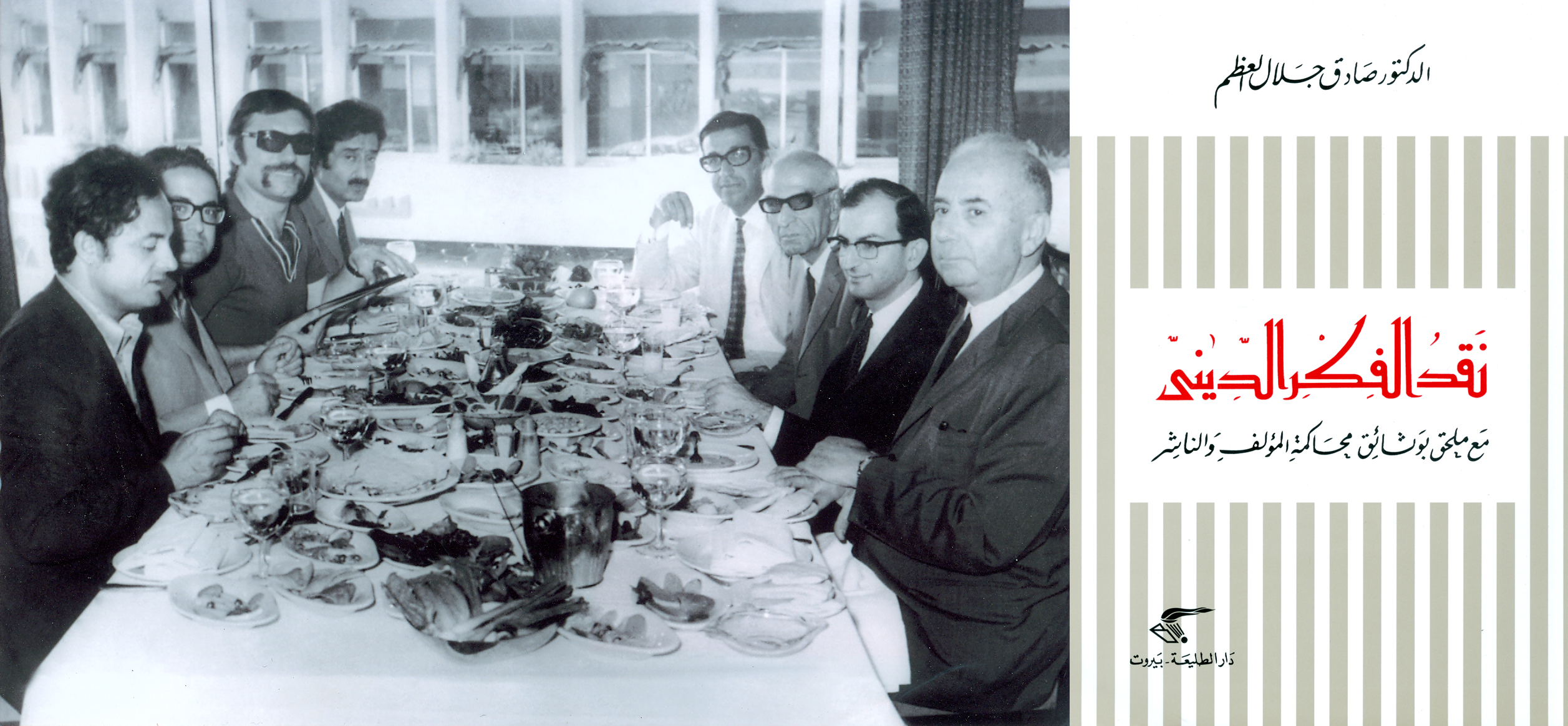

From left to right: Adonis, Joseph Mughayzel, Sadiq Jalal al-Azm, Aref al-Rayyes, Basim al-Jisr, Abdallah Lahoud, Bashir Daouk (publisher of Dar Al Talia), Edmund Rabbatt. Photo courtesy of Ms. Ghada Samman.

For over 40 years now, Sadiq Jalal al-Azm’s “Naqd al-Fikr al-Dini” (“Critique of Religious Thought”) has been one of the most controversial and influential books about the role of religion in Arab politics. Originally published in 1969 by Dar Al Talia and reprinted in 2009 by the same publisher, al-Azm’s work has been cited in countless articles and books about Arab politics and, according to the Qatari weekly, Al Raya, more than 1500 pages have been written about it. Though small sections of the book have appeared in translation in various works, the entire manuscript has never been fully translated into any of the major Western languages. However, the author has recently revealed that this will change in 2011, when an unspecified publishing house in the United States, and Editions Demopolis in France will finally make the book available to English and French speaking readers. Considering that its radical conclusions and timely subject matter contain a bold critique of religious and traditional thinking in the Arab world, it is incomprehensible that this book has remained un-translated for such a long time.

The criticisms put forth in the book are harsh, especially when considering the parameters allowed in past and current Middle East discourse. Al-Azm saw that the disastrous outcome of the 1967 War shattered both traditional religious thought and the exaltation of pan-Arabism, exposing the deluded thinking of many intellectuals of the time who were convinced that the secular and nationalist Arab regimes had the situation under control and were on the sure path to victory. His contention was that the swift defeat of the combined Egyptian, Syrian, and Jordanian armies at the hands of Israel was symptomatic of the failure of these regimes to synthesize outmoded religious dogma with mild socialism and progressive reforms. This unwillingness to more aggressively rethink the role of religion in society on the one hand, and steadfastly push social and political reforms on the other, ensured that the reforms that did get implemented during the 1950’s and 1960’s were superficial. If the Arabs were to achieve the same level of emancipation and development as their Western counterparts, they would have to seriously question the compatibility of traditional thinking with the concrete circumstances of the modern world.

After the publication of the “Critique of Religious Thought” in 1969, the Lebanese government imprisoned al-Azm and tried him for allegedly “inciting sectarianism,” a rather dubious charge considering that the book also questioned with equal rigor the inconsistencies in Christian thinking. In actuality, the crime he was really guilty of was his call for a critique of all aspects of Arab society, up to and including the misleading rhetoric of the monarchist, republican, secular, nationalist, and what were termed Arab progressive and socialist regimes. That he stirred up the ire of the Islamists and ruling regimes alike exposed the fact that the latter were concerned less with achieving progress and freedom and more with staying in power and maintaining the status-quo. His books are still widely banned in most of the Middle East, though they are certainly just as widely read.Speaking during a 1997 interview with Ghada Talhami, al-Azm suggested that there was a direct link between the failure of the ’67 War and what he considered a static approach to Islamic thought. According to al-Azm, “The Arab liberation movement was very guarded in its approach to Islamic thought, avoiding direct contact with it and ignoring the need to renew and rebuild it with openness and clarity. I was becoming very conscious of the ability of this body of thought to continually reproduce the values of ignorance, myth-making, backwardness, dependency, and fatalism, and to impede the propagation of scientific values, secularism, enlightenment, democracy, and humanism.” Al-Azm accused many intellectuals of performing tortuous acrobatics in order to interpret the Quranic scripture into the 20th century model of progress. He underlined the dishonesty and willful self-delusion in the idea that it was possible to reform Islam without performing a social, economic, and political overhaul of Arab society.

Sadiq Jalal al-Azm was born in 1934 to parents who were descendants of a prominent aristocratic Ottoman family from Damascus. Their admiration for Mustafa Kemal Attaturk and his brand of modern secularism deeply impressed him from an early age. His education reflects this – he received primary early schooling at protestant and French schools and went on to study philosophy at the American University of Beirut. Al-Azm subsequently received his doctorate from Yale, writing his thesis on the 18th century German philosopher Immanuel Kant. He would later write two books about Kant, both available in English. He returned to Beirut to teach at the American University in 1963, but was dismissed five years later following several controversial activities, which, among others, included the signing of a petition calling on the United States to leave Vietnam and the publication of his first book “Self-Criticism After the Defeat” (1968), the precursor to his “Critique of Religious Thought.” Al-Azm himself has speculated that the university’s refusal to renew his contract was heavily influenced by his differences with Professor Charles Malik, a pro-Western former Lebanese foreign minister and diplomat.

The most significant event during this part of his life, however, was the aforementioned publication of the “Critique of Religious Thought” in 1969, and the storm of controversy it ignited. For this he spent two weeks in prison, although he was freed after the Lebanese government was unable to substantiate its charges of sectarian incitement during trial. At this point, he went to Amman with the ostensible goal of teaching at the university there, only to find that his connections to the Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine had led to his name being put on the Hashemite monarchy’s blacklist. Out of options, he returned to Beirut to do research for the Institute for Palestine Studies, but the publication of another book “Critical Studies of Palestinian Resistance Thought” provoked the displeasure of the P.L.O. leadership. Arafat expelled him from the Institute and he was barred from publishing articles in its journal Palestinian Affairs (during the ‘80s, the journal’s editor, Anis Sayegh, allowed him to resume writing under a pseudonym).

In the ‘90s he taught Philosophy at Princeton for five years, and then did the same at the University of Damascus, where he was the head of the philosophy department. When he retired recently, he was quoted as laughingly having said, “they got rid of me and I got rid of them,” according to Hussein Hamza of the Beirut-based Al Akhbar newspaper. It is rumored that he had trouble returning to the United States to work at Princeton after the events of September 11. He is also well-known for his vocal defense of Salman Rushdie in the wake of Khomeini’s fatwa after the publication of “The Satanic Verses.” Indeed he was one of a surprisingly small number of Arab intellectuals to take this stance. The two books he wrote about this subject, “The Notion of Prohibition: Salman Rushdie and the Reality of Literature,” and “A Post-Prohibition Doctrine,” presented a vigorous defense of intellectual freedom in the Arab and Islamic worlds. It was clear that the Rushdie affair in many ways reminded him of his own trial in 1969.

“The Critique of Religious Thought” consists of an introduction, six chapters, and a supplement of material relating to the author’s indictment, trial, and not-guilty verdict. In the book, al-Azm criticizes religion, not as a spiritual phenomenon (as seen, for example, in the lives of Saints, Sufis, and philosophers), but rather as a force that interferes in our daily lives and influences the essence of our psychological and intellectual experience. It is the religion employed to determine the methods of our thinking, and our reactions to the world in which we live.

Al-Azm traces the decline of Christianity in the West back to four major events: the Renaissance, the revolution in scientific thinking from Copernicus to Newton, the advent of the Industrial Revolution, and the publication of Marx’s “Das Kapital” and Darwin’s “The Origin of the Species.” The challenges to and the skepticism of the myth of creation led to a fundamental shift in European culture. Religion had to make significant concessions to science in order to salvage some of its essential ideas and convictions. In stark contrast, the Middle Eastern response to scientific developments was not one of adaptation to new ideas, but rather one of reaffirmation of traditional thought on the basis of the idea that the Quran includes the totality of scientific knowledge. Al-Azm saw the impact of this religious thinking on the politics of his day: even secular leaders like Nasser were not willing or able to embrace Arab socialism without a religious justification. Unlike in the West, Arab socialism from its inception had to accommodate religious thinking rather than challenge it. He also criticizes the political use of religion, a process exemplified by the two drastically different regimes of Saudi Arabia and Egypt. In each country, the clerical establishment was critical to providing legitimacy for the government, doing so through the use of fatwas.

In the chapter titled “The Tragedy of Satan,” al-Azm explores the symbolic function of the mythology of the devil, analyzing it outside of its theological and spiritual contexts. Another chapter devoted to mythology, titled “The Miracle of the Virgin Mary’s Apparition and the Elimination of the War’s Consequences,” examines the reliance on superstition and mythological thinking in a contemporary context. In Egypt, the Coptic Pope Cyril VI claimed to have seen the divine apparition of the Virgin Mary in the Olive Church. This “miracle” was uncritically written about in all the newspapers of the Arab world, including progressive and secular publications. Furthermore, the press willfully disseminated the idea that the recurrence of the divine apparition somehow constituted proof that Jerusalem would be liberated. Al-Azm was appalled by the fact that it took a needless tragedy to put this religious hysteria to rest. It was only when many innocent people, including numerous children, were injured or trampled to death in a frenzied rush to see the place where the Virgin Mary had appeared that the Church publicly denied the miracle and was closed down by the government. Al-Azm was similarly astounded that there was not one single intellectual, socialist, secularist, literary figure, or journalist in the entire Arab world that had the wherewithal to denounce the whole affair from the outset. Rather than pointing out some of the very obvious contradictions in the evidence that was presented, they preferred to manipulate the religious inclinations of the people in an attempt to gloss over the military and political failure of the 1967 War. What was perhaps even more disappointing was that all the talk of science and progress that had been taking place before 1967 became totally obscured by the “Virgin Mary apparition.”

In the chapter “Distortions in Western Christian Thought,” al-Azm criticizes the tendency toward rationalization and justification taking place in Western Christianity as well. It is a response to the Philosophy Symposium “God and Man in Contemporary Christian Thought” that was held at the American University in Beirut (AUB) in late August of 1967, just two months after the Six-Day War, and was published as a book under that title in 1969. He was particularly suspicious of a lecture in which one of the Symposium’s participants claimed that the decline of the role of the Church and the concessions it made to its secular opponents did not constitute a defeat of the Church. On the contrary, the participant argued that the political power enjoyed by the Church did not rightfully belong to it in the first place. Al-Azm implies that there are some similar elements of rationalization in both Christian and Muslim Arab discourses, particularly in the impulse to turn a defeat into a victory.

When asked by the Qatari weekly, Al Raya (January 1, 2008), if he had changed any of his thinking since the publication of his “Critique of Religious Thought,” al-Azm made the observation that, if anything, the impoverishment of religious thinking is worse now than it has ever been. He recalls how in 1969 and 1970, many religious figures wanted to engage him in debate. Though they knew little to nothing about the concepts of modern science and technology, they grasped the necessity of addressing and understanding the social impact of these developments. He contrasts that situation to what is happening today, where certain fundamentalist groups reject outright anything that has to do with modernity, science, or the West. That the violent rhetoric of Jihadi groups has managed to overshadow the debate in and about Islam is due in large measure to the impotence of official institutions. The religious figures and intellectuals who represent these institutions tend to regurgitate the same rigid and nostalgic ideas in order to remain consistent with state policy. This creates a void that is easily filled by those who embrace the ideology of Islamist thinkers like Sayed Qutub. When al-Azm was asked by the same interviewer if he would revise anything in the book, he replied that the “Critique of Religious Thought” is a document of the period, and that he did not find it appropriate to change or substitute anything in it, especially since it has been available on the market since its original publication.

Nothing better describes the goal of the “Critique of Religious Thought” than the publisher’s statement on the back cover of the book: “Rarely does modern Arab thought attempt to openly challenge the intellectual structures and the dominant metaphysical ideology of our society, because penetrating this realm touches its most sensitive area, which is the religious question. But the contemporary Arab revolution cannot endlessly avoid addressing vital questions that are connected with metaphysical religious ideology and its relationship with the revolution itself – including all the problems that arise from reactionary Arab forces using religion as a major ‘theoretical’ weapon to mislead the masses. Thus, this series of critical studies of religious thought form a daring and necessary attempt by Sadiq Jalal al-Azm to destroy the dominant mythological mentality and substitute it with contemporary revolutionary and scientific ideas...”

This article appeared in Al Jadid Magazine, Vol. 16, No. 62, 2010.

Copyright © 2010 AL JADID MAGAZINE