I met Hanna Batatu in the mid-1980s, when I was a graduate student at U.C.L.A., where he lectured on Iraq. I and other colleagues interested in the politics and history of the Middle East met with him publicly and privately. Once while giving him a ride to the Los Angeles International Airport, he gave me his home telephone number, for he frequently worked at home when he did not have teaching commitments in Georgetown University. Sometime later I called him and asked if he would agree to be interviewed about the Kurdish question on a radio program hosted by a friend of mine. His answer was simply no, and for a while I thought he had refused because he did not want to bother with a minor media outlet, preferring the exposure of the major networks. However, over the years, and especially after the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait, it became clear that Hanna Batatu shunned the limelight, eschewing media, both major and minor.

This reveals some essential aspects of Batatu: he was humble and unassuming, fiercely protective of his time, and dedicated to the pursuit of knowledge.

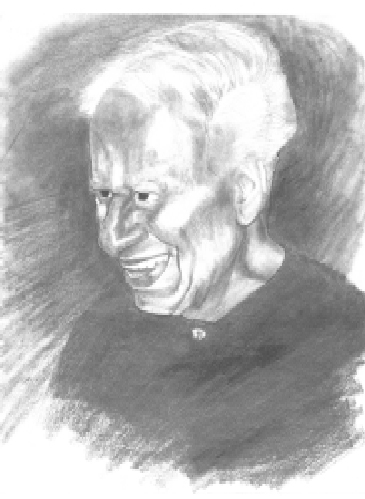

Hanna Batatu, 74, a leading authority on the contemporary Arab world best known for his writings on Iraq and Syria, died June 24, 2000, at his brother’s home in Connecticut after a brief battle with cancer. He passed away just a few days before American University of Beirut was going to honor him as one of its Millennium Scholars.

Ironically, the man who published what are considered masterpieces on the politics and history of both Iraq and Syria may actually be “under-published.” In addition to his “The Old Social Classes and the Revolutionary Movements of Iraq,” (Princeton, 1978), and “Syria’s Peasantry, the Descendants of Its Lesser Rural Notables, and Their Politics,” (Princeton, 1999), Batatu contributed articles to the Middle East Journal, the Middle East Report, and other publications. However, if one compares his publications to those of others, many of whom are not his intellectual equals, one will find Batatu under-published. His academic honesty prevented him from writing and rewriting the same articles a dozen times, under different titles, and with additional footnotes and acknowledgments.

Considered by many to be the leading political scientist to study the Middle East in the last half century, Batatu’s first major work was “The Old Social Classes and the Revolutionary Movements of Iraq” which draws on interviews with many out-of-office Iraqi political figures, either in Iraq or in exile. Many scholars consider this book to be one of the most significant works dealing with Middle Eastern society and politics published in recent times. Actually three volumes in one, it is one of the few books that has had an entire conference held to discuss it. The proceedings of that conference, which took place at the University of Texas (Austin) in March 1989, were published in 1991 under the title “The Iraqi Revolution of 1958: The Old Social Classes Revisited.”

The book — Batatu’s masterpiece — has maintained its place as one of the major works of history of the Middle East. According to Abbas Amanat, professor of modern Middle Eastern history at Yale, the interviews the book are based on provided Batatu “with a thorough and unique account of the events that otherwise would have been lost to historians.”

In 1999, Batatu published a counterpart to his Iraq study, “Syria’s Peasantry, the Descendants of Its Lesser Rural Notables, and Their Politics.” Dedicated to “the People of Syria,” the book traces the rural roots of Syria’s ruling Baath Party, exploring the characteristics and power structure of the Assad regime. As with his study of Iraq, he based the book on extensive interviews with individuals at all levels of Syrian life; it has been praised as a classic of rural history. Rashid Khalidi of the University of Chicago called it “a profound and comprehensive study of modern Syria that is unlikely to be surpassed for a very long time. It is a model of how social history should be written, and of how it can be used to explain the politics of a complex society like Syria.” In a review in the journal Foreign Affairs, L. Carl Brown, a Middle East historian, called the work “vintage Batatu, with awesomely thorough research,” and added, “This solid sociopolitical study of modern Syria’s rural population will take its place among the classics of rural history.”

His book on Iraq has elicited its share of criticism, both academic and non-academic. One scholar noted the over-empiricism that marks Batatu’s work on Iraq, depriving the student of an overall theoretical framework that can provide more systematic and rigorous explanations. The second common criticism is political, questioning the appropriateness of publicizing Iraqi Communist Party documents.

I am aware of no answer he gave to the first, but he had plenty to say on the second. On the first, I can only speculate that he might not have believed that the field of Middle East studies had matured enough to develop theories that can provide precise explanations and predictions about Arab politics. Batatu did not make unwarranted sweeping generalizations.

Regarding the Iraqi Communists, Batatu wrote in the preface of “The Old Social Classes and the Revolutionary Movements of Iraq,” that whenever he met Iraqi Communists who were political prisoners, they were informed that their personal police files were made available to him. They were also assured that because he was studying the party to which they belong, he was “impelled by no other motive than the desire to understand it and that, to the extent my limited vision permitted, I would be faithful to the facts and would publish the results whether they be to the advantage of the Communists or to their disadvantage.” Batatu admits that one of the Communist leaders he interviewed “wondered whether, in view of my connection with an American University, detachment on a subject like communism was at all possible.” In retrospect, Batatu insisted that it was. Abbas Beydoun wrote in the Lebanese daily As Safir, “No Arab political movement was given a lively narration like the history of the Iraqi Communist Party.”

Batatu’s teaching career was as rich as his scholarship. He was on the faculty of AUB from 1962 to 1981, and continued from 1982 until retirement in 1994 at Georgetown’s Center for Contemporary Arab Studies, where he held the Shaykh Sabah Al-Salem Al-Sabah Chair and was named Professor Emeritus upon retirement. He remained in the Washington, D.C. area until the fall of 1999.

While delivering the presidential address at the 1998 meeting of the Middle East Studies Association, a former student of Batatu, Philip S. Khoury, praised him as one of the “remarkable teachers and scholars at the AUB who set me (and many others) on the road of studying the Middle East. They are emblematic of a generation, a place, and a time.” Describing Batatu as having an “unusual, even threatening pedagogical style,” Khoury said and added, “he showed us that historians can operate at different levels of analysis and that one should never assume that a narrative does not require rigorous analysis.” Munah al-Solh, a prominent Lebanese intellectual, describes Batatu as one of “the few academics who succeeded in equally combining the roles of teacher and researcher.”

Born in 1926 in Jerusalem to a poor family, Batatu graduated from a French high school there. During the 1940s, he worked as a staff officer with the Palestine Mandatory Government in Jerusalem. In 1948, after the establishment of the state of Israel, he came to the United States where he worked for a carpet business in Connecticut while studying at Fairfield University. In 1951 he won a scholarship to Georgetown University’s School of Foreign Service where he graduated summa cum laude. Later he studied in Vienna, then received a doctorate in political theory at Harvard.

His life was unique indeed, according to several of his acquaintances. He remained single and did not socialize very much, devoting all his time and energy to scholarly research. When he taught at the AUB, he lived in the town of Shouwayfaat and Aynab, quite a distance from the university, and came to campus only to teach. He continued the same tradition when he taught at Georgetown, living outside the Washington, D.C. area. Even in his last days, he preferred to leave the hospital for his brother’s home to meet his “fate and inevitable destiny,” according to his former student, Hafez al-Sheikh Salih.

The death of Hanna Batatu was noted in The New York Times and The Washington Post, as well as many Arab language publications, but there are those who believe his accomplishments deserve more attention. Beydoun, the Lebanese poet and critic, noted, “A historian of world stature left us unnoticed; we will not think we feel the loss, for we do not think we need historians — or even history.”

This article appeared in Al Jadid Magazine, Vol. 6, No. 31, Spring 2000.

Copyright © 2000 AL JADID MAGAZINE