The Revolt of the Young: Essays by Tawfiq al-Hakim

Translated by Mona Radwan

Syracuse UP, 2015, 145 pp.

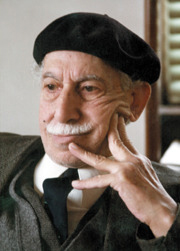

In 1984, Tawfiq al-Hakim (1898-1987) – a major literary and intellectual figure in Egypt and the Arab world who contributed to the development of Arabic literature – wrote “Thawrat al-Shabab” (“The Revolt of the Young”). The 20 chapters swing easily between al-Hakim’s past and present: recalling incidents from his past, discussing their relevance to his present, and examining the concerns of the younger generation. Mona Radwan translated the book into English for a 2015 publication date, four years after the January 25 Egyptian revolution. In the translator’s introduction, Radwan explains the importance of the timing of this publication, shedding light on this pioneering figure who predominantly contributed to Arabic literature through his novels, short stories, and plays. More importantly, Radwan discusses the gap between generations which ultimately leads to the young people lighting the spark in most revolutions around the globe. The 20 essays included in the book, most of them relatively short, have proven extraordinary harbingers of issues raised by events that occurred in Egypt over a decade after the author’s death.

In his “Introduction,” al-Hakim attempts to define the nature of revolutions (“thawra” in Arabic), distancing them from upheavals (a term chosen by Radwan to describe “alhoga” in Arabic). Young people lead every revolution as the representatives of youthful vigour, and although a revolution ultimately resorts to violence, it should retain that which proves useful, becoming a step in the natural evolution of rising nations. The revolt of the young, however, cannot be easily defined, for it is not based on specific demands, but rather is “the cry of the whole age...the awakening of an alarming future.” Even though al-Hakim’s book concerns the 1952 Revolution led by young army officers, it has equal relevance to other revolutions, such as the popular 1968 French revolt against De Gaulle’s regime, and the young Americans’ rejection of the Vietnam War. Al-Hakim’s uncanny abilities even extend to the foretelling of future youth-driven insurrections, such as the 2011 Revolution against the Mubarak regime, and the June 30, 2013 revolt against the Muslim Brotherhood regime.

Despite the fact that al-Hakim lived in an age of revolutions and coups d’état, “The Revolt of the Young” deals with more than the nature of revolutions, for it also focuses on his concern for the younger generation. Al-Hakim advocates the need to appreciate the works of young artists and writers, and investigates the responsibilities of the older generations, as well as the reasons behind the inevitable widening of gaps between the generations (exemplified in his relationship with both his father and his son), which lead to the eventual clashes and disregard that grow between them. He examines the role of nature in restoring balance, and the disparity between its laws and the attitudes and thought processes favoured by human beings. Furthermore, al-Hakim wonders if the new generation will be able to forsake the disastrous belief that “the end justifies the means.”

In the final chapter, provocatively entitled “The Case of the Twenty-First Century,” al-Hakim reflects upon the nature of young people’s revolutions, which traditionally begin with the youth’s “refusal of guardianship over their new lifestyle.” He believes that the young need to shoulder “their huge responsibilities to change the face of the world” and to disfigure the bad and ugly features of it. Although Radwan’s translation of “The Revolt of the Young” might look like a resurrection of days gone by, this voice from the past really offers counsel to today’s generation living in an age of political and social turmoil.

This review appeared in Al Jadid, Vol. 19, No. 69, 2015.

Copyright © 2016 AL JADID MAGAZINE